Buy Tin with 99.9% Purity Guaranteed

$32 000,00

Tin is the unsung hero of the periodic table. It doesn’t have the glamour of gold or the fame of iron, but it is the essential connective tissue of modern technology. From the Bronze Age sword to the iPhone circuit board, civilization has always relied on the bonding power of Tin.

As electronics continue to evolve, the demand for high-purity Tin solders will only increase, ensuring this ancient metal remains relevant well into the future.

Tin is often misunderstood. When people hear the word, they usually think of “tin foil” (which is actually aluminum) or cheap “tin cans” (which are mostly steel). In reality, Tin is a sophisticated, strategic metal that literally holds the electronic world together.

As the primary ingredient in solder, Tin is the glue of the digital age, connecting the microchips in every smartphone, laptop, and car on the planet. Without it, our modern electrical grid would simply fall apart.

This guide explores the unique characteristics, ancient history, and futuristic applications of this silvery metal.

What is Tin?

Tin (symbol Sn, from the Latin stannum) is a post-transition metal in group 14 of the periodic table. It is soft, malleable, and has a brilliant silvery-white luster.

Historically, Tin was one of the first metals mined by humanity. Its discovery led to the Bronze Age (approx. 3000 BC) when ancient smiths realized that adding soft tin to copper created a much harder, durable alloy: bronze.

Today, it is rarely used in its pure form for structural objects because it is too soft. Instead, it serves as a vital coating, alloy, and chemical agent.

Key Features of Tin

Tin possesses a distinct set of physical traits that make it irreplaceable in manufacturing:

- Corrosion Resistance: It does not rust or oxidize easily in air, making it an excellent protective shield for other metals.

- Low Melting Point: It melts at just 231.9°C (449.5°F), which is incredibly low for a metal. This makes it energy-efficient to work with.

- Non-Toxicity: Unlike lead or mercury, metallic Tin is generally non-toxic, which is why it is safe for food packaging.

- The “Tin Cry”: When a bar of pure Tin is bent, it emits a unique crackling sound. This “cry” is caused by the crystal structure of the metal breaking and reforming (twinning) under stress.

Why Choose Tin?

Engineers and manufacturers choose Tin not for its strength, but for its chemistry and connectivity.

1. The Universal Connector (Solder)

This is the primary reason the world needs Tin. Almost all electronic solders are tin-based (typically 95%+ tin). Because Tin wets and bonds to other metals (like copper and gold) easily without melting them, it creates the electrical pathways on printed circuit boards. If you want electricity to flow reliably between components, you choose Tin.

2. Food Safety (Plating)

Steel is strong but rusts easily. Tin is weak but safe and rust-proof. By coating a thin layer of Tin onto steel (creating “tinplate”), manufacturers get the best of both worlds: a strong can that won’t poison the food or corrode.

3. Perfectly Flat Glass

If you look through a window, you are looking through Tin. In the “Pilkington Process,” molten glass is floated on top of a bath of molten Tin. Because Tin is dense and perfectly flat in its liquid state, the glass cools into a perfectly flat sheet without the need for polishing.

Applications of Tin

The uses of Tin are surprisingly high-tech and diverse.

1. Soldering (Electronics)

Roughly 50% of all Tin produced globally acts as solder. Following the ban on lead in consumer electronics (RoHS compliance), pure tin or tin-silver-copper solders have become the industry standard for smartphones, computers, and medical devices.

2. Tin Chemicals

Tin compounds are used in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics. They act as heat stabilizers, preventing PVC pipes, window frames, and siding from degrading under the sun’s heat.

3. Alloys (Bronze and Pewter)

- Bronze: A mix of copper and Tin (usually 12%). It is used for ship propellers, statues, and musical instruments (cymbals and bells) due to its resonance and seawater resistance.

- Pewter: A malleable metal alloy used for decorative tableware, consisting of 85–99% Tin.

4. Li-ion Battery Anodes

Researchers are currently exploring Tin as a material for next-generation Lithium-ion battery anodes. Tin anodes can theoretically store more energy than the current graphite anodes, potentially leading to longer-lasting EV batteries.

Properties of Tin

Here is the scientific data for this post-transition metal.

| Property | Value/Description |

| Chemical Symbol | Sn |

| Atomic Number | 50 |

| Appearance | Silvery-white, lustrous, soft |

| Density | 7.31 g/cm³ |

| Melting Point | 231.9 °C (449.5 °F) |

| Boiling Point | 2,602 °C (4,716 °F) |

| Mohs Hardness | 1.5 (Very soft, can be cut with a knife) |

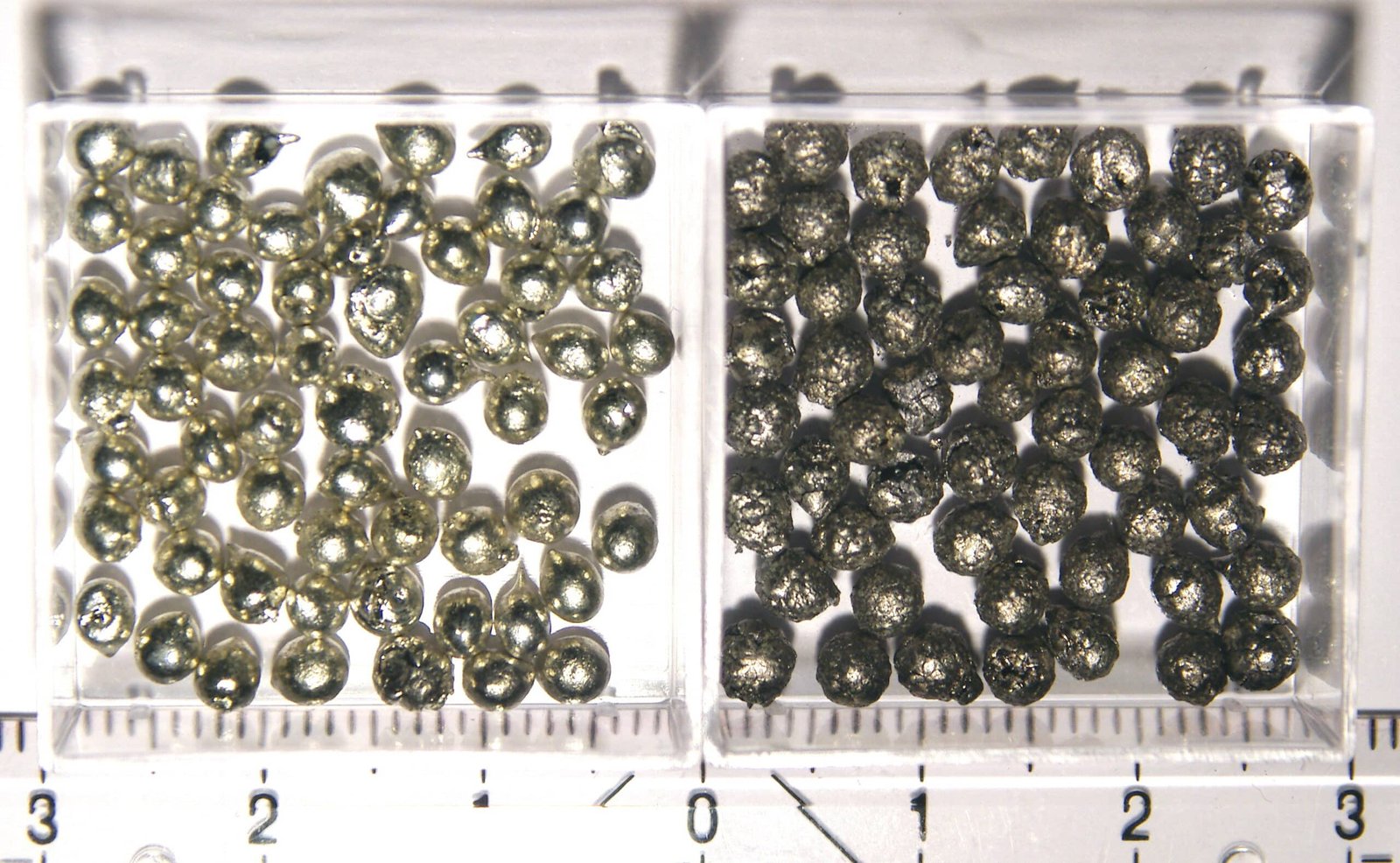

| Allotropes | White Tin (Beta) and Gray Tin (Alpha) |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Is “Tin Foil” actually made of Tin?

Not anymore. Before the 20th century, foil was made of Tin. However, after World War II, aluminum replaced it because aluminum is cheaper, lighter, and does not impart a “tinny” taste to food. Today, we still call it “tin foil” out of habit.

What is “Tin Pest”?

Tin has a strange weakness. At low temperatures (below 13.2°C), shiny metallic “White Tin” can spontaneously transform into a brittle, gray powder called “Gray Tin.” This phenomenon, known as “Tin Pest” or “Tin Disease,” famously caused the buttons on Napoleon’s soldiers’ coats to disintegrate in the freezing Russian winter.

Is Tin toxic to humans?

Elemental Tin is considered non-toxic. However, certain organic tin compounds (organotins) used in agriculture and industry can be toxic. This is why the interior of tin cans is often lined with a lacquer to prevent any chemical leaching, just to be safe.

Is Tin a rare metal?

Tin is relatively scarce compared to iron or aluminum. It is primarily mined in China, Indonesia, and Peru. Because it is essential for electronics but hard to find, it is often listed as a “critical mineral” by governments concerned with supply chain security.

Be the first to review “Buy Tin with 99.9% Purity Guaranteed” Cancel reply

Related products

RARE EARTH & INDUSTRIAL PECIOUS METAL

RARE EARTH & INDUSTRIAL PECIOUS METAL

RARE EARTH & INDUSTRIAL PECIOUS METAL

RARE EARTH & INDUSTRIAL PECIOUS METAL

RARE EARTH & INDUSTRIAL PECIOUS METAL

RARE EARTH & INDUSTRIAL PECIOUS METAL

RARE EARTH & INDUSTRIAL PECIOUS METAL

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.